Magnetic Superstructure Phase Induced by Ultrahigh Magnetic Fields

PI of Joint-use project: M. Gen

Host lab: Kohama and Y. H. Matsuda Group

Host lab: Kohama and Y. H. Matsuda Group

Magnetic superstructures, where the magnetic unit cell is an integer multiple of the original crystallographic unit cell, have received considerable attention. For frustrated spin systems, a variety of quantum-entangled magnetic superstructures can appear in an external magnetic field. Of particular interest are a series of magnon crystals in the spin-1/2 kagome Heisenberg antiferromagnet [1] and successive transformations of singlet-triplet superstructures in the spin-1/2 orthogonal-dimer Heisenberg antiferromagnet [2]. Furthermore, the interplay between spin and lattice degrees of freedom can induce spin–lattice-coupled magnetic superstructures, as theoretically proposed for the Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the breathing pyrochlore lattice, where neighboring tetrahedra differ in size in an alternating pattern [3]. In this study, we verify this theoretical prediction in a model compound of the breathing pyrochlore antiferromagnet, LiGaCr4O8, by means of state-of-the-art magnetization and magnetostriction measurements under ultrahigh magnetic fields up to 600 T [4].

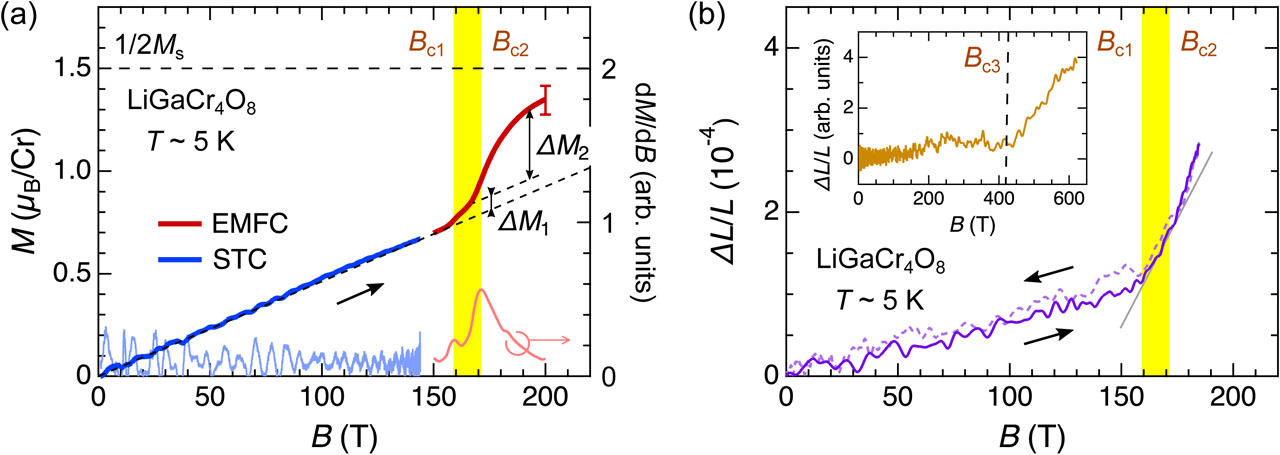

Figure 1(a) summarizes the magnetization data of LiGaCr4O8 measured at ~ 5 K. In the single-turn coil (STC) system, we observe a linear increase in the magnetization M with respect to the external magnetic field B up to a maximum field of 145 T, suggesting that spins are smoothly canting from the 2-up-2-down collinear ground state. Upon the application of a higher magnetic field using the electromagnetic flux compression (EMFC) system, we observe a dramatic magnetization increase between 150 and 200 T, followed by a half plateau at M ~ 1.5 μB/Cr, as reported in conventional chromium spinel oxides [5]. Notably, a double-hump structure can be seen in dM/dB, indicating a two-step metamagnetic transition at Bc1 = 159 T and Bc2 = 171 T. The existence of an intermediate-field phase is supported by the magnetostriction measurement. Figure 1(b) shows the magnetostriction data measured at ~ 5 K using the STC system. The sample length starts to rapidly increase at Bc1, then the lattice expansion accelerates above Bc2. We also measured the magnetostriction up to 600 T using the EMFC system, as shown in the inset of Fig. 1(b). A plateau-like behavior is observed from 200 T up to Bc3 ~ 420 T, followed by an upturn behavior up to the saturation around 550 T. The observation of a wide plateau suggests the strong spin–lattice coupling inherent in LiGaCr4O8.

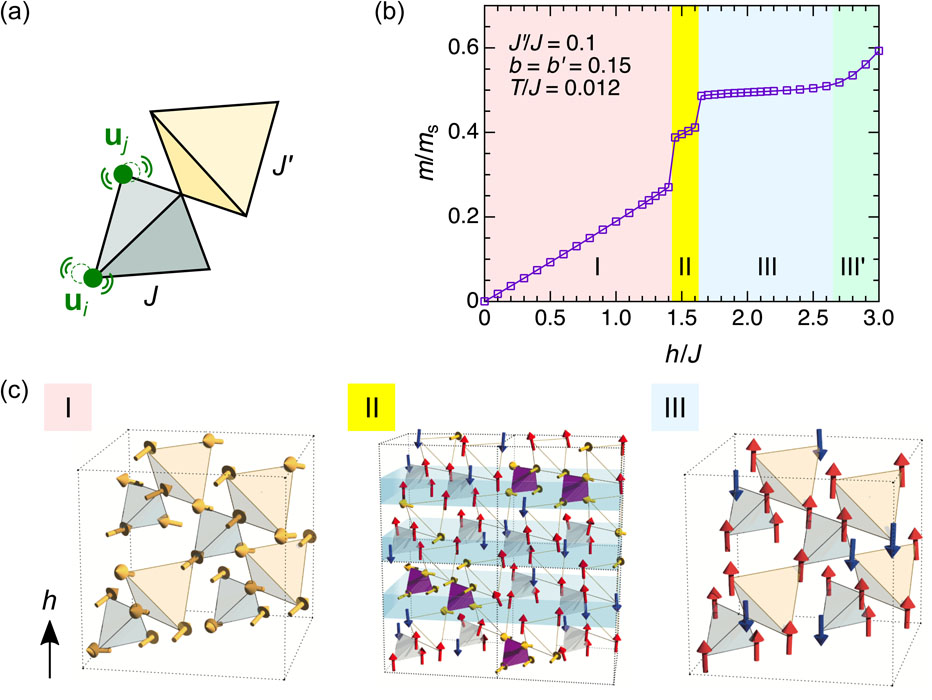

To understand these observations, we perform the classical Monte-Carlo simulations for a magnetoelastic Hamiltonian on the breathing pyrochlore lattice, incorporating the Einstein site-phonons [3,4]. Figure 2 shows the calculated magnetization curve obtained for a typical parameter set with relatively large breathing anisotropy and strong spin–lattice coupling. In addition to the low-field phase (Phase I) with an 8-sublattice canted 2-up-2-down state and the 1/2-plateau phase (Phase III) with a 16-sublattice 3-up-1-down state, an intermediate-field phase (Phase II) appears, associated with a two-step metamagnetic transition. The magnetic structure of phase II is characterized by a three-dimensional periodic array of canted 2-up-2-down and 3-up-1-down tetrahedral clusters in a 1:2 ratio, forming a magnetic superstructure with a 6 × 6 × 6 magnetic unit cell.

In summary, we experimentally demonstrate that the breathing pyrochlore antiferromagnet exhibits unconventional field-induced phase transitions, which could signal the emergence of a magnetic superstructure phase. The present work, combining the exotic experimental observations with the microscopic magnetoelastic theory in a complicated three-dimensional frustrated magnet, paves the way for further verifications of intriguing physical phenomena originating from the spin–lattice coupling and/or breathing anisotropy, both of which can be relevant in magnetic materials regardless of the geometry of the underlying crystalline lattice.

References

- [1] J. Schulenburg et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 167207 (2002).

- [2]. K. Kodama et al., Science 298, 395 (2002).

- [3] K. Aoyama et al., Phys. Rev. B 104, 184411 (2021).

- [4] M. Gen et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2302756120 (2023).

- [5] A. Miyata et al., J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 114701 (2012)