Theoretically Predicted Collective Excitation Modes in the Quadruple-Q Magnetic Hedgehog Lattices

PI of Joint-use project: M. Mochizuki

Host lab: Supercomputer Center

Host lab: Supercomputer Center

The Kondo-lattice magnets are recently attracting enormous research interest as hosts of rich topological magnetism. This class of magnets have localized spins coupled to itinerant electrons via exchange interactions, and the itinerant electrons mediate long-range RKKY-type interactions among the localized spins. A variety of topological magnetic textures, e.g., skyrmion crystals, meron crystals, hedgehog lattices, emerge as superpositions of multiple spin helices or spin-density waves with different wavevectors determined by the Fermi-surface nesting.

Recent intensive studies have rapidly clarified equilibrium phases and static properties of the Kondo-lattice magnets, and several new materials have been discovered and synthesized experimentally. However, their nonequilibrium properties and dynamical phenomena remain unclarified yet. Under these circumstances, we have started the research for their spin-charge dynamics and related phenomena based on large-scale numerical simulations using the supercomputer facilities in ISSP, University of Tokyo. Through these studies, we have revealed many interesting dynamical phenomena, e.g., microwave-induced magnetic topology switching [1], unexpected spin-charge segregation in the low-energy excitations of a zero-field skyrmion crystal phase [2], photoinduced magnetic phase transitions to 120-degree order [3], and peculiar collective excitation modes of hedgehog lattices [4].

Among them, the last one is the most recent achievement. Three-dimensional topological magnetic structures called magnetic hedgehog lattices (Figs. 1(a) and (b)) have been discovered recently in several itinerant magnets such as MnGe, MnSi1-xGex and SrFeO3. The research on magnetic hedgehog lattices to date has focused mainly on their properties at equilibrium. On the other hand, according to the fundamentals of electromagnetism, magnetic (anti)hedgehogs, which behave as emergent (anti)monopoles, should generate emergent electric fields when they move. Therefore, clarification of their excitation dynamics will directly lead to the discovery and exploration of new emergent phenomena and device functions of topological spin textures in dynamical regimes.

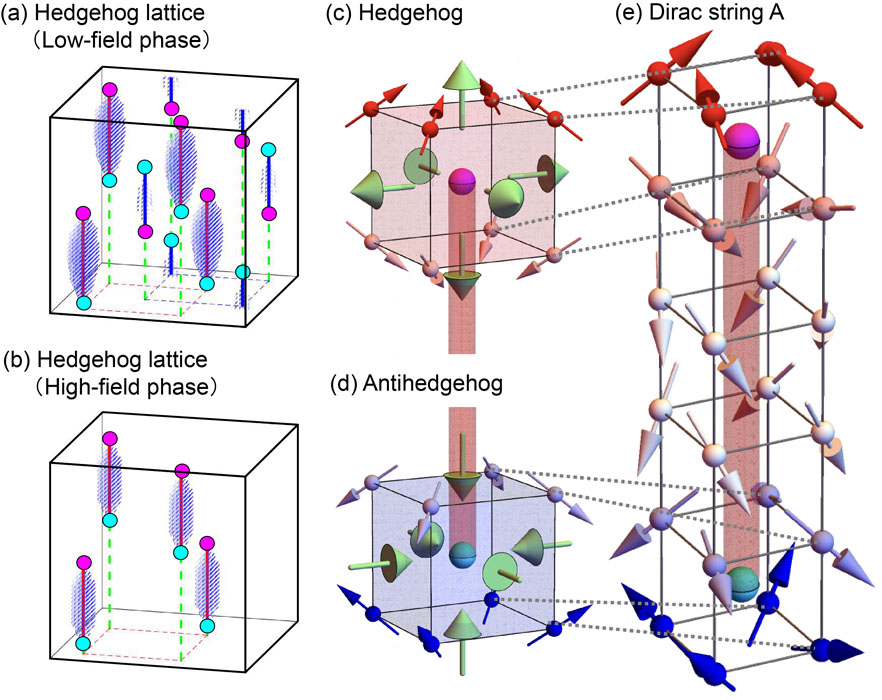

Fig. 1. (a), (b) Spatial arrangement of hedgehogs and antihedgehogs in magnetic hedgehog lattices. The magenta and cyan dots represent the hedgehogs and antihedgehogs, respectively. The lines connecting them represent Dirac strings. There are two types of Dirac strings (red line: Dirac string A, blue line: Dirac string B) with distinct magnetization winding senses. In the zero-field and low-field hedgehog lattice, both Dirac strings A and B exist (a). On the contrary, when the applied magnetic field exceeds a certain threshold value, the Dirac strings B disappear, and a hedgehog lattice with only Dirac strings A appears (b). (c), (d) Magnetization configurations (red and blue arrows) and distributions of emergent magnetic fields (green arrows) for a hedgehog and an antihedgehog. The hedgehog behaves as a source of the emergent magnetic fields, while the antihedgehog behaves as a sink of the fields. (e) Magnetization configuration of the magnetic vortex (Dirac string A) connecting the hedgehog and antihedgehog.

Motivated by this aspect, we investigated the nature and properties of collective excitation modes expected when the quadratic-Q hedgehog lattices realized in MnSi1-xGex and SrFeO3 are irradiated by light by means of numerical simulations using a microscopic theoretical model. In the magnetic hedgehog lattices, hedgehogs (Fig. 1(c)) and antihedgehogs (Fig. 1(d)) are connected by a magnetic vortex called Dirac string (Fig. 1(e)). As shown in Fig. 1(e), the spins below the magnetic hedgehog go rotating down to the antihedgehog to form a vortex structure connecting the hedgehog and the antihedgehog. Because the rotating sense of the vortex is two-fold, there are two types of Dirac strings, which are right-handed and left-handed. Although two types of Dirac strings do not necessarily appear in a single material, in the case of the hedgehog lattices realized in MnSi1-xGex, there are indeed two types of Dirac strings (A and B) with different winding senses.

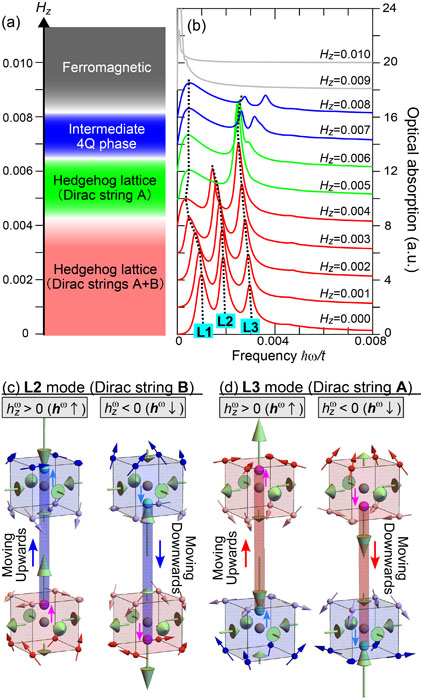

In the theoretical work reported in Ref. [4], we discovered that there exist three collective excitation modes (spin-wave modes) in terahertz to sub-terahertz frequency regime, which we named L1, L2 and L3 modes (Figs. 2(a) and (b)). Further analyses revealed that for the L2 and L3 modes, in-phase oscillations of the hedgehog and antihedgehog located at upper and lower ends of the Dirac string occur to exhibit translational oscillation, that is, the Dirac strings move upwards and downwards in an oscillatory manner (Figs. 2(c) and (d)). It is well-know that when a bar magnet is moved closer to or further away from a metallic coil, an electric voltage is generated. It is interesting that the collective translational oscillations of the Dirac strings discovered here are the equivalent motion as that of the bar magnet in this case. In other words, in light-irradiated magnetic hedgehog lattices, a huge number of nano-sized bar magnets show such oscillatory motion at high frequencies of terahertz or sub-terahertz orders.

Fig. 2. (a) Phase diagram as a function of the external magnetic field Hz. At zero and low magnetic field, a hedgehog lattice with both Dirac strings A and B appears. As the magnetic field is increased, the hedgehog and antihedgehog belonging to the Dirac string B annihilate, and a phase transition occurs to a hedgehog lattice consisting of only the Dirac strings A. (b) Calculated optical absorption spectra. Three peaks correspond to collective excitation modes (named L1, L2, and L3) at the eigenfrequencies. The values of frequencies are written in normalized units, and these modes appear in a frequency range of approximately several hundred gigahertz or sub-terahertz. Looking at the L2 and L3 modes corresponding to the Dirac-string oscillations, both L2 and L3 modes appear in the low-field hedgehog-lattice phase where both Dirac strings A and B exist. On the contrary, in the high-field hedgehog-lattice phase without Dirac strings B, the L2 mode originating from the Dirac strings B disappears and only the L3 mode originating from the Dirac strings A remains. (c) Translational oscillations of the Dirac string B in the L2 mode. (d) Those of the Dirac string A in the L3 mode. The hedgehog and antihedgehog at the upper and lower ends of the string exhibit in-phase oscillations, which cause vertically translational oscillations of the strings.

More interestingly, among the three oscillation modes, we found that the L2 mode corresponds to the oscillations of the Dirac strings B (Fig. 2(c)), while the L3 mode corresponds to those of the Dirac strings A (Fig. 2(d)). Consequently, we expect that the L2 (L3) mode vanishes when the Dirac strings B (A) disappear. In fact, application of a magnetic field can realize the selective disappearance of the Dirac strings B through inducing hedgehog-antihedgehog pair annihilations (Figs. 1(a) and (b)). We indeed observed that the L2 mode vanishes upon this field-induced annihilation of the Dirac strings B as seen in Fig. 2(b). This means that the external magnetic field can switch these collective oscillation modes, which enables us to realize on-off of the emergent electric fields and transmission of microwaves at corresponding frequencies.

Our discovery of the collective excitation modes of emergent magnetic (anti)monopoles in condensed matters is of importance from the viewpoint of fundamental science. Moreover, the discovery is expected to open the way to designing the optical/microwave device functions and spintronics functions of the three-dimensional topological magnetism that can be controlled and switched by external fields.

References

- [1] R. Eto and M. Mochizuki, Phys. Rev. B 104, 104425 (2021).

- [2] R. Eto, R. Pohle, and M. Mochizuki, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 017201 (2022).

- [3] T. Inoue and M. Mochizuki, Phys. Rev. B 105, 144422 (2022).

- [4] R. Eto and M. Mochizuki, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 226705 (2024).